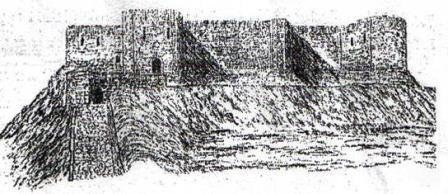

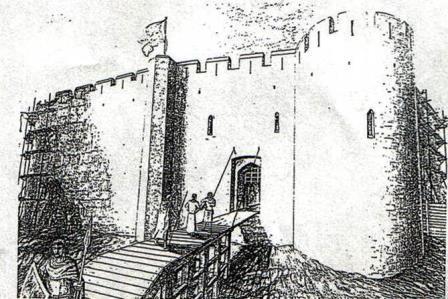

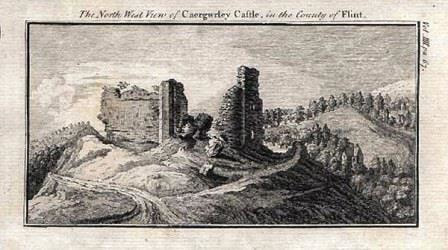

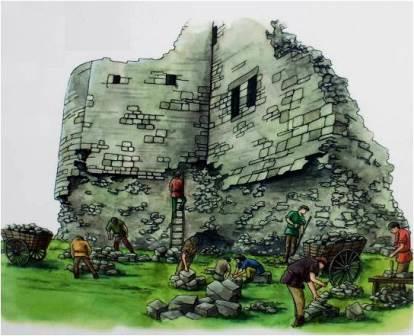

Approximately a hundred local people and visitors (only some of whom are pictured) enjoyed the Halloween Ghost and Mystery Tour of Caergwrle Castle which was organised by the Caergwrle and District Community Action Group.The tour was given by the ‘ghost’ of Prince Dafydd ap Gruffydd, Lord of Hope and the original builder of the Castle. He was also the first person in British history to be ‘hung, drawn and quartered’ for the crime of High Treason. Photograph by Charlene Harston of Caergwrle & District CAG Those present heard chilling stories of the 27 Welshmen whose heads were taken to the Castle in return for payment of one shilling each, several ghostly heads being on view as they ascended the Castle Hill. They also heard that the period of archaeological excavation unearthed bones which included those of a black rat; a discovery which provided a cue for involvement of children in a hands-on Black Death activity. However, the adults present were invited to grapple with the key mystery of one of the most enigmatic castles of Wales: how did people actually enter Caergwrle Castle in medieval times? Discussion of this issue was the backbone of GCSE History coursework for local secondary school children for a number of years.  One of the suggestions made was that the main entrance was through the East Tower. The idea is supported by the absence of a defensive moat at this point and the height of the archway from the tower to the inner ward. The archway is much higher than normal for a tower doorway and suggests that it was constructed for a person on horseback. However, the presence of a fireplace, directly opposite the suggested entrance, suggests that any heat generated by the fire would be lost once the door was opened. Thus the point that now serves as the main point of entry for the Castle may or may not have been the original gateway.  Another suggestion was that the main entrance was at a point between the North Tower and the buttress by the East Wall. Although there is a well-worn route across the moat nowadays, this theory involved a combination of a drawbridge and wooden footbridge to gain access to the inner ward at a point, next the well, where a small set of steps now exists. This was an idea which curried some favour before the archaeological excavations of 1988-1990, which seemed suggest a more likely possibility for the main gateway.  This appeared to be a rock outcrop which had been left deliberately so as to create a confined area in front of the gateway, the weakest point of the castle. The current Castle interpretation panel includes an illustration, by Anne Robinson, of what this may have looked like at the time.  The idea developed that a small defensive structure had been constructed on the mound to act as an added defence to the north of the gateway. This was believed to have been one of the modifications, made by King Edward I, in the rebuilding of the castle in 1282-83. Edward’s diggers, of whom 600 were recorded, had extended the area of the moat, leaving the rock outcrop in situ. This, it was argued, had then been connected to the northern bank of the new moat extension by a raised footbridge. The ‘barbican mound’ served to concentrate any enemy forces in a confined space so they could then be picked off by archers from the northern wall of the Castle battlements. Further entry, for friendly forces, was afforded by a drawbridge, which linked the mound to the gateway in the Castle’s northern wall. The gateway was therefore through the northern wall.  However, Charles Evans-Gunther has now perceptively challenged the conventional wisdom of this theory. By drawing attention to the drawing of the Castle which was made by Samuel and Nathanial Buck in 1742, which Charles states ‘doesn’t seem to show this barbican mound.’ The illustration is interesting and does show several features of the Castle as they may well have been it 1742. The main features, which stand today, of a buttress-supported east wall, part of a north tower, part of a northern wall and even a local house, Plas yn Bwl, are clearly evident. Interpretations of what is shown immediately to the north (or to the right) of the North Wall may differ. There is a raised bank shown, but this seems to be the bank of an un-extended moat rather than the ‘barbican mound’. If we are to take the illustration at face value it suggests that the extension to the moat, which is evident today, actually occurred after 1742, and not as part of the modifications made by Edward I.  The Castle itself was plundered for stone to be used for local building materials and the area to the west of the site has been quarried extensively. The current interpretation panel includes an illustration of stones being robbed from the North Wall of the Castle during the seventeenth century.  One is left with the possible conclusion that the extension of the moat which created a ‘barbican mound’ was actually caused by quarrying of stone, which took place during the period after 1742. Charles Evans-Gunther has opened up a debate which adds interest to the mystery of the original location of Caergwrle’s gateway. It is, of course, possible that the main entrance to the Castle was through the North Wall, but the defensive ‘barbican mound’ seems to have received a bit of a battering. It could be that this is a mystery that may never be solved. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.

0 Comments

|

AuthorDave Healey Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed