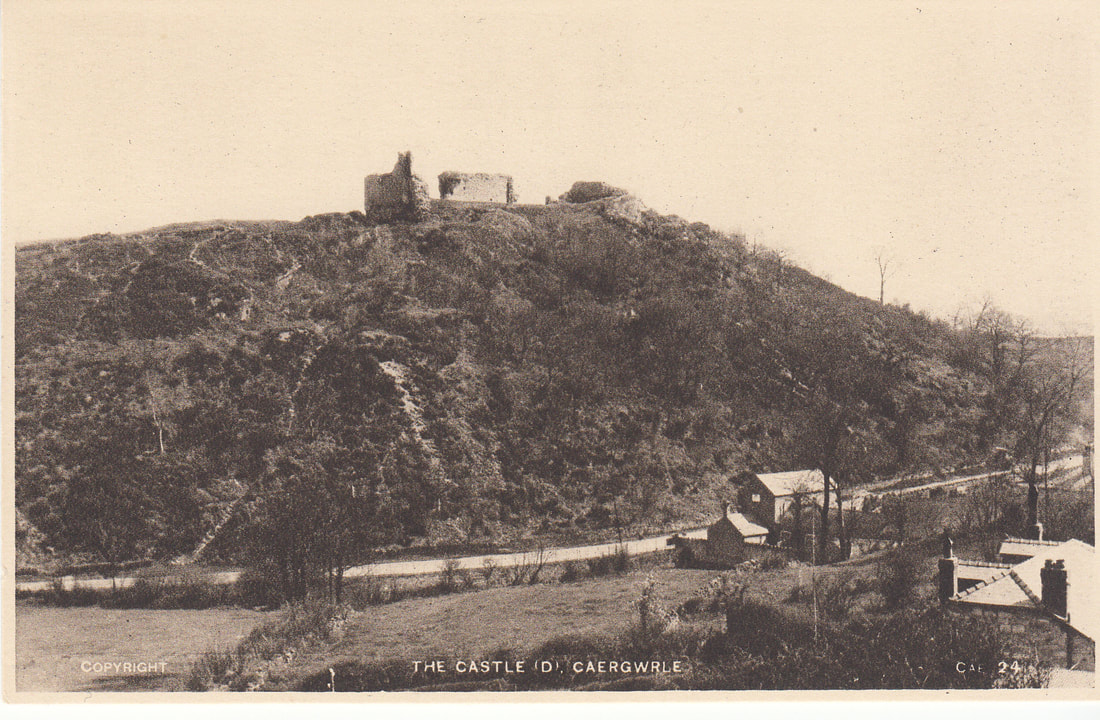

The tremendous downpour of rain in mid-June came as a surprise. It closed roads, disrupted rail travel and led to the issue of 4,000 sandbags across Flintshire alone. A fortnight later I visited my daughter in the south of England and experienced pretty unbearable heat of the hottest day of the year so far. Crazy weather? You can say that again! There are some important implications for aspects of Our Heritage in what is clearly an era of climate change. The first point is undoubtedly the risk posed to our valued Scheduled Ancient Monument of the Packhorse Bridge which spans the River Alyn between Hope and Caergwrle. The story of the Bridge has been well documented in previous articles. It was constructed in the third quarter of the seventeenth century as part of the on-going improvement in communications which foreshadowed the era historians have dubbed the ‘Industrial Revolution’. In the November 2000 it was virtually destroyed when the arches became blocked and it crumbled under the weight of a tremendous amount of floodwater. The damage done exposed a cast iron active sewer pipe, which is embedded in the footpath. Fortunately this was not damaged by falling masonry and the River Alyn was spared the impact of the prospect of a local environmental disaster of a sewage spillage. The blocked arches had caused the flood water to back up causing flooding in the homes of adjacent properties in Sarn Lane. Their relief from this misery only came when the Bridge itself gave way and released a huge amount of water into the downstream section of the river. The Bridge was subsequently restored at a cost of £100,000 by Welsh Government and Flintshire County Council. Experts from Natural Resources Wales (NRW) provided every assurance that, on the basis of their modelling an episode like that of 2000 could not happen again for another 70-90 years. The pressure was off, it seemed. There was no urgency for anyone to respond to local lobbying about the need for action. However, this June we came very close to a similar experience as the arches became blocked, once again with large tree trunks and a mass of miscellaneous debris, including a trampoline from a nearby garden. The water level built up until the actual footpath across the Bridge itself became flooded. The Bridge, with its structure weakened by the growth of vegetation and the long–acknowledged need for re-pointing, was at risk once again. Luckily the rain stopped and the flood water subsided. Every credit must be given to the group of local people who gathered at the Bridge to free the arches once the flood had subsided and the river level lowered. This was a tremendous feat of local heroism. They cleared large fallen trees and a massive amount of debris so that the river could flow freely. There is, of course more work to be done to ensure the safety of the structure but the experience of mid-June shows that the authorities cannot rest on their laurels. This is the first lesson for Our Heritage from the impact of climate change. The second lesson for Our Heritage is more contentious but remains a fact. We can draw lessons from the flooding experience of mid-June and revise some of our perceptions about what is best for Our Heritage. This article includes the well known photograph of Caergwrle Castle on a bare, treeless outcrop. Whenever this photograph appears on social media it provokes a number of nostalgic yearnings for the days when the Castle could be seen, by all, for miles around. It also provokes comments about the desirability of cutting down the trees in order to achieve this idealised view of the monument once again. These yearning are based on a misconception about what is best for the environment and for our community. Indeed, it is likely that a return to a barren hilltop, even if this were legally permissible within the Conservation Area, would pose a serious threat to homes in the immediate vicinity of Castle Hill within the current context of climate change. The recent flooding caused serious problems along several roads which are adjacent to the lower slopes of Hope Mountain. A blocked culvert failed to carry water from Hope Mountain and caused the Mold Road to be closed near the junction with Pentre Lane. A vehicle was left stranded and there was a flood risk to local properties. Relief came when local people secured the help of someone with a digger who broke through a hedge in order to excavate a means of releasing the flood water from the roads. Llanfynydd Road on the west side of Hope Mountain was closed through flooding and people living in Gwalia, in Caergwrle, were mindful of previous flooding that has occurred there. Whilst Sarn Lane, Caergwrle, was flooded by water from the River Alyn, these other examples occurred at the bottom of an upland area which is partly farmed and not covered in trees.

The significance of upland woodland is that, according to the Woodland Trust, the extensive root systems of trees allow for sixty times more penetration of rainwater into the ground itself than would otherwise be the case. A bare hilltop at Caergwrle would inevitably cause large amount of water to roll down the hillside with a serious risk of flooding of adjacent roads and homes. Indeed there are times when fallen trees on the Castle Hill have actually caused a flow of water to emerge from the sponge-like ground that has absorbed the rainfall. Any tree-felling at all at the site has to be done judiciously and with consideration of the possible consequences. The Welsh Government has now declared a Climate Emergency and has recognised that climate change threatens our health, economy, infrastructure and our natural environment. The bid to deliver a low carbon economy involves planting trees, rather than removing them. Flintshire Countryside Services have been ahead of the game with their Urban Tree and Woodland Plan for 2018- 2033. This sets a target to establish urban canopy cover of 18% (as opposed to the 2013 figure of 14.5%) by 2033. Flintshire is currently the seventh lowest county in Wales in terms of tree canopy cover so there is a feeling that some headway needs to be made. The current trend is therefore to plant trees, rather than to remove them. To view Flintshire Countryside Service’s Plan, which has the approval of full Council, see: https://www.flintshire.gov.uk/en/PDFFiles/Countryside--Coast/Tree/Tree-Plan.pdf The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of either Flintshire County Council or Hope Community Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.

0 Comments

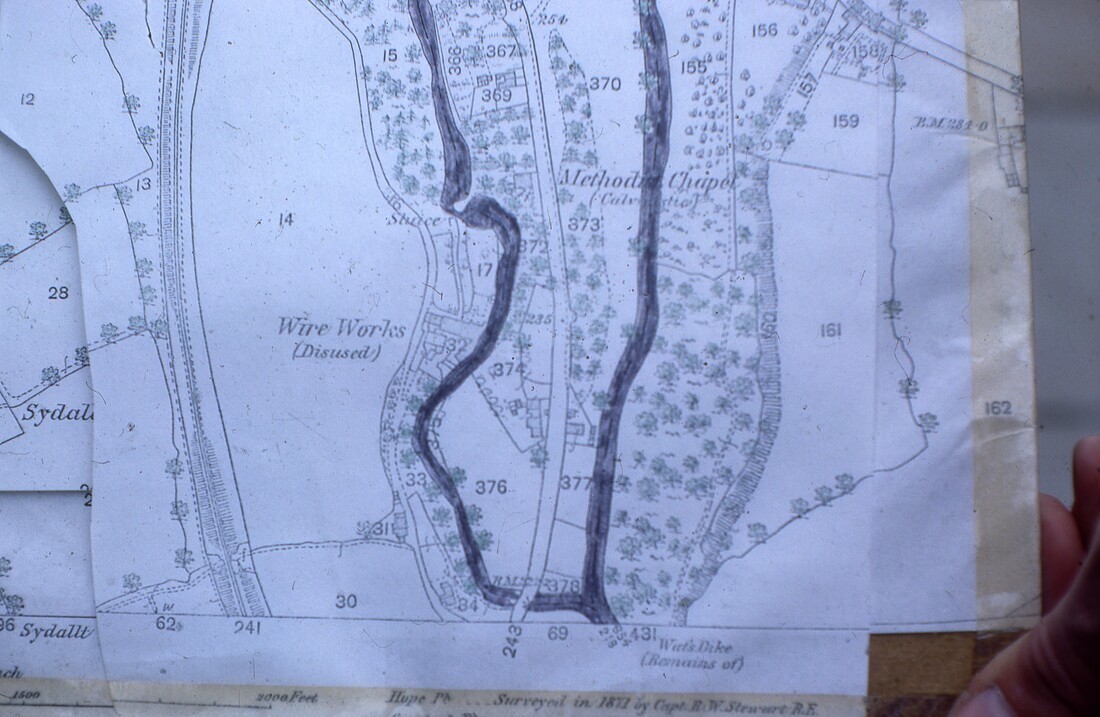

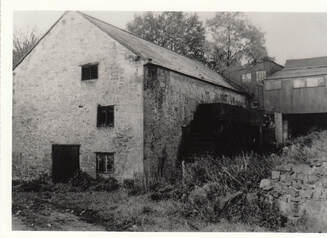

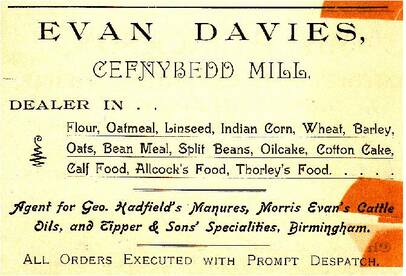

This month I am indebted to Christopher Jones who, having read some of the articles on Cefn-y-bedd and Abermorddu which have appeared in the Hope4All Magazine, has provided me with a CD of photographs of parts of an old local map which used to adorn the wall of one of the classrooms in the old primary school in Abermorddu. It may be that local readers, who were pupils at the school, will remember such a map on the wall. The map is a copy of the one which was surveyed by Captain R. W. Stewart of the Royal Engineers in 1871. In 1979, when the photographs were taken, Christopher was employed by the then Clwyd County Council Architects Department as a decorator and was required to remove everything from the classroom walls before painting the walls and ceilings. He spotted the map, and recognising it was of great local interest, he brought his camera to work and, with the help of a colleague, they took the board, to which the map was attached outside to be photographed. The blue tinge on the photographs is probably due to the film having deteriorated since 1979. Flecks on the pictures are probably small particles of dust which were on the map. Whilst it may well be possible to obtain clearer images of the 1871 map from other sources, it interesting that two individuals felt that it was important to preserve part of our heritage in this way. It is also interesting that the staff of Abermorddu School also felt that it was important to give pupils a sense of place and a sense of belonging by displaying their heritage on the classroom wall. I have chosen to include two of the maps from the CD in this article because they provide an opportunity to comment upon two local industries, one of the River Alyn and the other on the Cegidog, which are generally overlooked. They were nevertheless, important sources of local employment in bygone times. Firstly we have a map which shows the position of Hope Paper Mills, which were located by a millrace from the River Alyn and are marked ‘disused’ on the 1871 map. For further information on these mills we must turn to A History of Hope and Caergwrle by Rhona Phoenix and Alison Matthews. Whilst this is the seminal work on the two villages it is also a very important source of information on the somewhat neglected communities of Abermorddu and Cefn-y-bedd. Phoenix and Matthews explain that water was directed to the works along a narrow concrete channel forcing it to flow faster onto an internal waterwheel. At a later date, as was generally the case with early industry, it was made redundant by the introduction of the stream engine. The authors found the earliest reference to paper making ‘in Hope’ to be 1811, with Samuel Price named as the paper maker five years later. In 1842 a ‘new’ paper mill was being operated by R.C. and J.H. Rawlins until the late 1880s. Apparently the business produced small, hand, fine and unglazed papers as well as blue and brown paper for bags. They also noted that in 1843 a female paper glazier earned 2s. a week and a paper sorter 3s. In 1880 an agreement was made with Llay Hall Colliery for the paper mill to use their branch railway line to transport raw materials and finished products. Apparently the mill was sold in 1890 for £1,050 and the contents and machinery were sold separately for low prices as the machinery was, by then, antiquated. The ‘disused’ site marked on the 1871 map is presumably the site of the former mill, which dated from at least 1811, with the ‘new’ post 1842 mill being the building slightly to the east and adjacent to the millrace.  The second industry which is of interest is that of the Wire Works shown along the banks of the River Cegidog. This too is marked as ‘disused’ in 1871. Once again we can turn to the invaluable book by Phoenix and Matthews for further information on the works. They note that it was built downstream from the Cefn-y-bedd corn mill on the River Cegidog and was known as the C.F.B. Wire Mill, producing winding ropes for the local collieries. It was therefore one of the industries which developed as part of the supply chain for an industry which was of such great importance to the area in former times. Apparently in 1782 the Overseers of the Poor Law paid 6s. to the mill, probably to support a pauper boy as an apprentice. Whilst Phoenix and Matthews state that the closure date of the mill is unknown it does appear on an old map of 1835, which can be viewed online, and is not marked as disused at that time. Thanks again must go to Christopher Jones for the photographs which have provided a stimulus for this article. It may be that there are other readers who have something to contribute, especially with regard to the neglected stories of Abemorddu and Cefn-y-bedd. If so please do get in touch. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  Our thanks this month goes to Violet Bell for permission to reproduce her excellent photograph of the houses along Stone Row in Abermorddu. John Trematick, the late local historian, associated these houses with the local mining industry and, given the importance of the coal industry as a source of local employment, he was probably correct. The row of houses have been referred to locally as ‘Hayes Row’ and they were probably built by Edwin Hayes who had a building business further down the road by Cefn-y-bedd station. The Wrexham Advertiser of 1st May, 1875 included an announcement of the auction of the whole stock-in-trade and household items of Edwin Hayes on 4th May 1875. Clearly the business was being wound up by then so the houses of Stone Row will pre-date that event. Unlike the Stone Cottages of Cefn-y-bedd, the houses of Abermorddu’s Stone Row do not appear to be identified by either that name or the name of Hay’s Row in census material and it is difficult to actually identify household occupants and their occupations. Coal mining was of considerable importance as a means of local employment in bygone times but there is now little physical evidence that this was the case. Our mining heritage is fast disappearing. As Llay Main Colliery operated from 1923 until as late as 1966 there are still a number of local people who worked there. Attempts were made to sink a shaft at Llay Hall as early as 1845 but water ingress made it difficult to do this with any success until 1877. By 1896 this colliery was employing 276 miners and 84 surface workers, but the problem of water ingress, it was finally forced closure to take place in 1947. The first shafts associated with the Gresford Colliery were sunk in 1908 and mining went on there until closure in 1973 on economic grounds. Gresford was, of course, the pit associated with the terrible disaster of 1934 when one of the worst underground explosions in British history claimed the lives of 266 men. The grave of local man Evan Hugh Jones, who died as a result of this tragedy, can be seen in Hope Old Cemetery. As with Llay Main Colliery, there are several residents alive today who have an association with the colliery at Gresford. However, our mining heritage is more extensive than this: the North Wales Coalfield was a productive vein and was the leading sector of the industrial revolution in the area. A list of collieries operating in 1881 includes ones at Ffrwyd, Gwersyllt, and the Wrexham and Acton one at Rhosddu. Also on the list is one at ‘Hope’, which is also sometimes referred to as Gwern Alyn Colliery. This colliery was located within very close walking distance of the Stone Row cottages. The exact date of the establishment of a colliery at Hope is unknown. In researching information for his book on ‘The Miners of Llay Mine’ Vic Tyler-Jones actually found evidence of mining at Hope actually going back as early as 1353 when lead and coal mines were rented out for £3 a year. Another source has produced some details of accidents in Hope Colliery between the years of 1775 and 1776, and although these details are rather vague, we do know that several people were killed or injured as a result of burning, sulphurous inhalation and blasting accidents. There were no accident books in the early years and one really does wonder about the untold agonies and horrors that miners experienced, especially in an era when child labour was the norm. We are reminded of the grave of 10-year old Owen Jones that can be seen in Pontblyddyn Churchyard. He died as a result of a Leeswood mining accident. Hope Colliery receives a mention in some of the booklets by John Trematick which are held in the Local Heritage Archive in Hope Community Library. In particular, John mentions a time when another, now deceased local resident, Denis Martin, took him to the derelict winding engine house of Hope Colliery. Hope Colliery closed in 1881 but Denis had worked in the engine house building making fireplaces for Alyn Fireplaces. John noted that the building had a plaque with ‘Lilleshall 1876’ on it. This he said was misleading because Lilleshall bought the business in 1876 but the engine winding house was actually constructed earlier. Denis also showed John were the old mine shaft was. It was fenced off and filled with rubble from the spoil bank. The two men also saw the base of the huge brick pillars which supported the bridge which carried coal wagons from Llay Main colliery to the sidings at Caergwrle. Denis recalled how busy it was with the coming and going of of colliery wagons along the line in his early years. There will be other residents in the locality who have similar memories. Attempts were made by local people to establish a right of way along what was called the Gwern Alyn Footpath where land has been fenced off by private landowners. Unfortunately the claims were dismissed after a public enquiry was held in Caergwrle Presbyterian Schoolroom. It is a pity we have lost a possible footpath that would have enabled us to see part of our industrial and transport heritage. Thankfully the old winding engine house still stands today tucked away behind On the Tiles in Cefn-y-bedd. It is no longer a derelict building and has been preserved as a family home. Together with the important memories of John Trematick and Denis Martin it is one of the few remaining pieces of evidence of Hope Colliery. There is a catalogue of items lodged in the Local Heritage Archive which may be seen at Hope Community Library. It is then possible to ask the Librarian or volunteers to see individual files or booklets such as those by John Trematick. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  This month thanks go to Mr and Mrs Jones of School Cottages in Abermorddu for allowing me to photograph the well in their garden opposite Old School Court. The well is fed by an underground stream which was once a more prominent feature locally and even flooded at times. The stream is an important feature for two reasons. Firstly, it is almost certainly the distinguishing feature which contributed to the origins of the place-name of Abermorddu itself. The authorities are not in complete agreement over the exact derivation of the place-name but they do agree that it involves a brook or a stream and that the term ‘aber’ relates to its confluence with the River Alyn. Ellis Davies, Canon Emeritus of St. Asaph Cathedral, in ‘Flintshire Place-Names’ states that the term is derived from ‘the black brook that joins the River Alun’. However Hywl Wyn Owen and Ken Lloyd Gruffydd, the highly acclaimed authors of ‘Place-Names of Flintshire’, discuss the linguistic contortions of the term and plump for ‘brook by the dark bare hill.’ Our heritage can be a stick of dynamite at times. People are rightly precious about it because it gives them a sense of identity and belonging. I will therefore leave it to the reader to decide which interpretation they prefer. The second reason why the stream or brook is important is because it marks the boundary between Abermorddu in the ward of Caergwrle and Cefn-y-bedd in the ward of Llanfynydd. Thus part of the garden of Mr and Mrs Jones is in Abermorddu and part in Cefn-y-bedd. There has been considerable misunderstanding about where Abermorddu ends and Cefn-y-bedd begins, even amongst those who live there. The main cause of this misunderstanding would appear to be the fact that when the original Abermorddu Primary School was built it was, indeed in Abermorddu. The stream actually runs under the road from the home of Mr and Mrs Jones and behind the current Old School Court. When the new school was built in Cymau Lane the name was retained. However Cymau Lane is actually in Cefn-y-bedd. Thus Abermorrdu School is in Cefn-y-bedd and not Abermorddu! The electoral ward of Llanfynydd is itself divided into further wards for purposes of election to Llanfynydd Community Council. Thus 266 electors live in the community ward of Cefn-y-bedd. The specific details of relevant roads are: Alundale, Cymau Lane, Ffrwd Road, Hawarden Road, Holly Bush Bach, Holly Court, Llay Road, Llys Clark, Llys Cromlech, Mold Road, Petit Close, Plas Mein Drive, Red Dragon Caravan Site, Wrexham Road and Wyndham Drive. All of these roads lie to the south of the stream which has been used as the physical featu8re to separate them from Abermorddu. My apologies to any residents there who may be suffering an identity crisis as a result of this revelation!

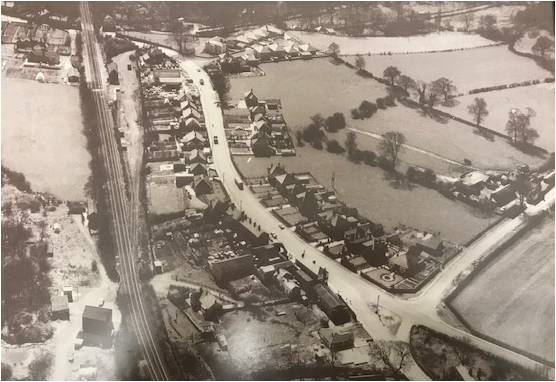

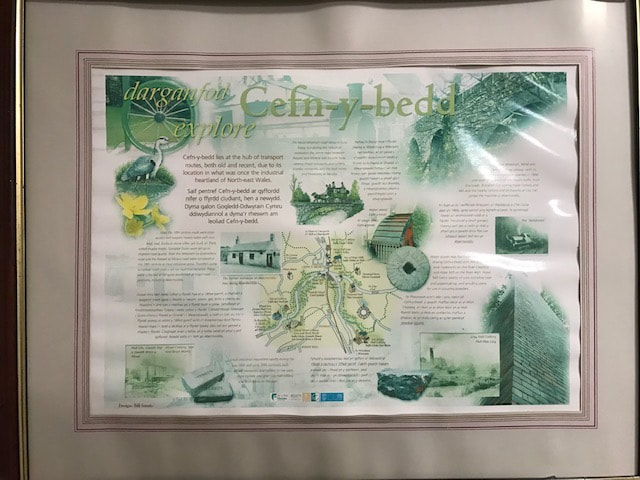

Thanks also go to Mr and Mrs Jones for allowing me to copy an aerial photograph of the area which was taken in 1963. The photograph shows a number of interesting features which may well be the subject of a further article. I will leave it to the reader to decide which parts of the photograph are in Abermorddu and which are in Cefn-y-bedd! The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  Thanks are due this month to George Sumner for providing a copy of a 1930s photograph of Hawarden Road, Abermorrdu and also to Mrs Eleanor Williams for her own childhood reminisces of the road in the first part of the twentieth century. Old photographs of Abermorddu are not nearly as plentiful as those of Hope and Caergwrle and one from the 1930s is particular welcome because few people had cameras in those days. The photograph is actually two photographs which have been joined together to show the row of council houses which still stand in Hawarden Road. They will have been amongst the first to have been built in Britain in as a result of Lloyd George’s government’s Housing Act of 1919, the first piece of legislation to provide government subsidies for the building of council houses. It was deemed necessary so that the government could meet a target of 500,000 new homes over a three-year period. They were to be ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ who had returned from the various battle fronts of the First World War. Local people have confirmed that members of their own families moved into the houses around 1924 when they were considered to be new. There was a further Act in 1924 that gave a new lease of life to council house building but these ones were already built by that date and we must therefore conclude that they were amongst the first to be built. Abermorddu was a prime site for building because of its strategic position on the North Wales coalfield and the employment opportunities which it provided. One only needs to glance at the 1911 census to sense that the coalmining industry was the single most important source of employment in the locality. Household after household has some connection with the coal industry. Wages may have been low but the work was there. For those moving in search of work there was an urgent need for homes and the private sector was not meeting the demand. The photograph shows two forms of transport: the horse and cart and an early model of a Ford motor car. This is a picture of Britain on the verge of a transport revolution that will usher in dramatic changes. We now know of the huge benefits of the motor car but also of the many issues of concern that have emerged since the photograph was taken. Mrs Eleanor Williams has childhood memories of horses and carts along Hawarden Road in the first half of the twentieth century. The milk was delivered by horse and cart. In an era when nobody bothered about health and safety the driver used to let young children sit on the seat and drive the horse down the road. The photograph also shows an early model of a Ford car, possible a model T. This would have been a rare sight and it is almost certainly the reason why the photograph was taken. Few people would have been able to own one of these in the 1930s and a small sign at the front of the vehicle suggests that it may actually have been a delivery vehicle for a local business. One other tell-tale sign in the photograph is the rather dilapidated state of the front garden walls. Could it be that the houses themselves were in need of repair after a decade of having been built? The minute book of the Hope Parish and District Ratepayers’ Association is particularly illuminating on this issue. The minutes of the meeting of 9th December, 1929 states: “The Secretary brought to the attention of the meeting the condition of the council houses stating that water was penetrating through the doors and windows of some of the houses in large quantities and the tenants were suffering great discomfort through lack of repairs. A member who is a tenant of the council houses added to this stating that he had written complaining about the state of his house but had received no reply to his letter from the Hawarden Rural District Council.” The Ratepayers took up the case and it was reported to the next meeting, of 13th January 1930, that repairs to the council houses of Abermorddu were being undertaken. There were no further complaints about the condition of the houses in the minutes that immediately followed with the exception of a comment that it was necessary for fences to be provided for the gardens. Funding actually ran out for completion of the initial house building scheme and it is unlikely that the government will have provided for repairs and maintenance. The rents received from tenants will not have been sufficient to cover the cost of repairs in the early years, giving rise to a backlog of repairs and maintenance issues. We know from elsewhere in the minutes that there was a lack of funding for road repairs because of the loss of government grants. Britain was in the throes of the years of Depression. The council houses represented the beginning of a ribbon development which ultimately connected Abermorddu to Caergwrle. As new homes were built so too were the shops which served them. There were no supermarkets and everyone did their shopping locally. It was important that the needs of local people were met. Mrs Williams remembered collecting milk in a jug from the Abermorddu Farm in Cymau Lane at a time when Wyndham Drive was itself farmland. Across the road was the Toll Bar Store where she collected the bread and next door was the café which was housed in an old wooden building. This provided afternoon teas for day trippers and also accommodation for those who chose to stay longer. The traffic lights and the garage by the lights were a sign of the times as cars became more frequent down Hawarden Road, although Mrs Williams remembered children collecting car registration numbers as a hobby whilst they were still something of a novelty. Beyond Abermorddu School was the Cooperative Store, which later became Castle Motors, and is now a newly built house. Further along was Theo Hopwood’s Store and then a small sweet shop by Coronation Terrace, where the Tin Chapel also stood. Across the road was Pugh’s Yard where local builder Alan Edwards had his business. Then there was Castle Farm and also another general store on the same side further along. Mrs Williams remembered several shops opposite the station itself: hairdressers, a fish shop, sweet shop and a shop which sold supplies for decorating. Her childhood memories were pleasant; it was a time when everyone knew everyone else. The residents in the houses shown in the photograph can be proud that they now live in houses which a played a significant part of the social history of the locality. Thanks again to those who have contributed information that enables us to preserve these aspects of the Abermorddu story. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  A Miller’s Tale There has, for some time, been an old photograph of a mill amongst a number of local photographs which came into my possession. Whilst I have identified most of the others this one mystified me. It felt that I should know where it was but I didn’t. The Facebook page of Old Photos of Hope, Caergwrle, Abermorddu and Cefn-y-bedd soon solved the problem. I posted the photograph and asked for suggestions. Within a few minutes I had the answer: it was the old flour mill of Cefn-y-bedd. Social media is a double-edged sword but thanks to one of the benefits I also discovered the story of the mill. I am indebted to Andy Davies and several other commentators who recognised the photograph immediately. Andy’s father had been ‘Lew the Mill’ who had worked there since leaving school. He joined the RAF in 1938 and then continued working there after the Second World War. It is clear that the Mill had been a family business for successive generations. Andy’s Taid was Maelor who worked there and before him, Maelor’s father, Evan Davies worked the Mill. Following on from these leads I checked the Census for 1911 and found Evan Davies, described as the Miller of Cefn-y-bedd. He had been born in 1858 and was aged 53 at the time. His wife, Annie Moyan Davies, had been born in 1872 and was 39. A daughter, Lydia, was aged 23 with an occupation of ‘Dress work’. Then there was, indeed, Andy’s own Taid of Ed Maelor Davies, aged 18, ‘helping at mill’ and a younger brother, Evan Cardry, aged 16, whose occupation had a similar description. A further younger brother, Robert, was aged 7 at the time of the census. By coincidence I was then contacted by Ian Swain who asked me if the Local History Archive at Hope Community Library would like a copy of the 1902 ‘History of Caergwrle Castle and Neighbourhood’ by H. D. Davies, an early Head of Abermorddu School. As soon as Ian brought it round I spotted it carried an advertisement for Evan Davies of Cefn-y-bedd Mill. Another piece of the jig-saw had come into play. I now knew that Evan was a dealer in flour, oatmeal, linseed, Indian corn, wheat, barley, oats, bean meal, split beans, oilcake, cotton cake, calf food, Allcock’s food, Thorley’s food and that he acted as agent for Hatfield’s Manures, Morris Evans’ Cattle Oils and Tipper & Sons Specialities from Birmingham. The census showed that Evan was born outside the area so we must assume that he was the first of the family line to operate the Mill. He had certainly built up a well-connected business by 1902. It was also notable from the advertisement that the business had diversified to a considerable degree. Flour and oatmeal would have been produced by the milling process itself but Evan was obviously a dealer in other specialist supplies brought in from elsewhere.  Evan’s advertisement promised that all orders would be executed by prompt dispatch. In 1902 this would have meant by horse and cart. However, an anecdote passed down the Davies family, shows that things did change a generation when his son, Maelor, ran the Mill: the age of the motor car had arrived. In brief, the story is that there was a younger member of the family who seized the opportunity to drive Maelor’s brand new car whilst he was away. Unfortunately he crashed it into a hedge and Maelor, upon his return, had to use the Mill’s wagon to tow it out of a field. The Mill relied on waterpower and was run by water from a millrace from the River Cegidog off the Ffrwd Road. However, the goods associated with the business were being transported by wagon. The area is referred to as ‘Little Liverpool’ by local people who have shared their childhood memories of going there to play or to get corn for the chickens. It was damaged by fire in the 1960s and was derelict until the 1980s. However it is now restored as a private home with two external waterwheels preserved. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  A Potted History of Cefn-y-bedd One has to be impressed by the series of interpretation panels that adorn the walls of the entrance to the Holy Bush public house in Cefn-y-bedd. There is one on the story of the Ffrith, one on Pontybodkin and one on Llanfynydd. These are well written and well illustrated. There is also another one which only approximately half of the pub’s visitors will generally get the chance to see. It is the one depicting the story of Cefn-y-bedd itself and it is to be seen hanging on the wall of the gentlemen’s toilet. It seems only right, in an era of equality of opportunity that the secrets of this panel should be made known for the benefit of all. It may come as no surprise that the panel concentrates on two themes, which, in different ways, are as important today as they were in earlier times: the importance of transport links and the importance of the world of work. The Holybush is situated at what, can be at times, a particularly busy road junction, the A550 Mold to Wrexham road taking quite a hammering from early morning and evening traffic. It is not uncommon for people to sit in standstill traffic, by the A550/B5102 junction complaining about hold-ups on social media. The road network, especially at this junction, was also of concern before the eighteenth century. There were problems of carts, carrying raw materials of coal, lead, iron ore and stone and finished products like bricks, becoming mired in the mud tracks along roads which were no longer fit for purpose. The upkeep of roads was a tremendous burden on the parish and the system was simply not coping with the problem. The eighteenth century solution was to allow private companies to establish turnpike trusts which would establish a network of tollhouses along the roads, charge for their use and thereby maintain the roads. Whilst this precipitated a backlash in the form of the Rebecca Riots in some parts of Wales, where there were certainly abuses of the system, there is no evidence of similar occurrences in north Wales. An old photograph of the tollhouse of Abermorddu, which was built in the eighteenth century, to collect charges for the use of the road at this point, features prominently on the panel. Pointing to another road link which was previously important the plaque states: ‘The Mold-Wrexham road remains busy today but during the period of the industrial revolution the minor road between Rossett and Minera was equally busy serving Ffrwd ironworks and colliery, Brymbo ironworks and the local mines and limeworks of Minera.’ Continuing on the theme of transport links the panel then describes the importance of the arrival of the Mold and Connah’s Quay railway, with a station at Cefn-y-bedd, by 1866. This would take some of the heavy freight traffic from the roads. There was a branch line to Hope Colliery, which was an important source of local employment behind the current Alyn Fireplaces as well as Hope Mill. There was also a branch line to the colliery and brickworks of Llay Hall, which joined the mainline at Abermorddu. The railway is still a vital link is to be hoped that improvements in the Bidston-Wrexham line, including an increase in frequency of the service will help to alleviate some of the current-day problems of congestion. The network of transport links, together with the main buildings of the period are skilfully depicted on a map which forms the centrepiece of the panel. Thus we see the site of the former Hope Colliery, the Toll Gate, Railway Station and railway viaduct, Hope Mill, Holly Bush, Gwastad Farm, Gwastad Hall, the site of Llay Hall Colliery, the site of Ffrwd Colliery and Brick works, road to Brymbo and Ffrith, the Ffrwd Inn (formerly the Red Lion), another colliery adjacent to the public house, Sydallt Wood, the site of the former flour mill of Cefn-y-bedd and Plas-Maen. Whilst evidence of many of these buildings and features can still be seem it is fascinating to see them depicted together in this way. The panel does describe the expansion of local industries in the nineteenth and early twentieth century’s. There are old photographs of Ffrwd Colliery, Iron and Brickworks, of some of the stamped bricks produced, of Llay Hall Colliery and of a piece of coal that had been hewn from it. Excellent drawings depict a horse and carriage crossing the bridge and also the waterwheel that was another feature of old Cefn-y-bedd. Waterpower was harnessed to drive the corn mill and rope works along the River Cegidog and Hope Mill along the River Alyn. Hope Mill had a number of uses including rope and paper making and grinding stone for scouring purposes. The Cefn-y-bedd panel is certainly an attractive piece of artwork which summarises and depicts a potted history of the community in limited space. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.

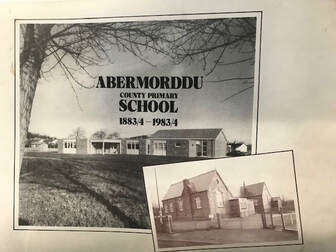

Remembering Abermorddu County Primary School There have been a few nostalgic muses about the old school of Abermorddu on social media recently and this seems like a good opportunity for an article which reflects upon the story of that building. The location of the building has been preserved by the name ‘Old School Court’ and the original date stone of 1882 is now encased in the wall of the more modern building in Cymau Lane. Unfortunately much of Abermorddu’s history is becoming a distant memory. The school provides a good starting point in rectifying this problem. Thanks must go to a previous Head, Mr Ian Swain, for preserving the story in the centenary publication of the school in 1983/4. This, in turn, owed something to an earlier Head, Mr R. W. Edwards. A copy of the centenary publication is to be found in the Local Heritage Archive in Hope Community Library. The booklet explains how the school came to be built. The Education Act of 1870 represented a landmark commitment to education in Britain but it did mean that more schools would have to be built in order to ensure provision on a national scale. In 1880 a further Act was passed which made school attendance compulsory for children up to the age of 13. This increased the urgency for schools to be built. Locally the newly established Local School Board found that there were 1,029 children between 3 and 13, of whom 92 were aged from 5 to 13 in the area covered by the Board. This area must have been quite large as the three schools which existed at the time were at Llanfyndydd, Bridge End (Hope) and Bwlchgwyn. The figures suggested the need for a new school with the Cefn-y-Bedd area being favoured. Eventually the site at Abermorddu was put forward as being the closest feasible option. The land was purchased in 1882 for the price of £365 and the tender went to local builder, Mr Probert, to build the school for £1380, although the total cost of building eventually reached £2,000. It was to accommodate 230 children. The first Head of the school was Mr H. D. Davies and he kept a log book from 20th August, 1883, the first day of opening. By the end of the day he and two assistants had enrolled 85 children. The number had risen to 134 by 12th September, with some coming from across the boundary with Denbighshire. Until 1891 these children will have paid school fees of about 2d a day and large families found this difficult. The centenary history records the future Heads as follows: Mr J. O. Smallwood 1910-1919, Mr J. E. Rogers 1920-39, Mr Howell Jones 1939-1958, and Mr R. W. Edwards 1958-1978. Mr Edwards saw the evacuation of the old building to a permanent building for Infants and Juniors mobiles in Cymau Lane. Mr Bryn James 1978-1983 was Head when the new building was started. The James took up an appointment at Cartrefle College and Mr Ian Swain was Acting Head until his appointment in 1983.  Early comments in the press said that it was a ‘fine building and surroundings’ but one letter writer commented on the provision of one large room and a small classroom. The writer felt that the voices of the teacher and children would echo in a room with a high ceiling and suggested a folding partition, based on examples seen in America. The example consisted of wooden sections with panes of glass, although a cheaper one could be made with hessian on the frames. The partition was later fitted in 1896 and was remembered by Albert Prydderch who first attended the school from Ffrwd in 1946. “The main part of the school contained three classrooms, by way of two large wooden and glass partitions that could be pulled back to make one large hall.” The arrangement allowed for versatile use of the space in a number of early schools and readers may well recall this being the case in their own primary, or secondary school. The centenary history also captured the memory of one resident who was obviously a pupil at the school when it was still an unimproved Victorian building. This anonymous writer was at the school from 1926-28, and had moved from a more modern school building in Llay: “First reactions on entering Abermorddu School were somewhat disappointing. It was very old-fashioned, very Victorian and lacked the amenities of our previous new elementary school in Llay which had opened in the Autumn term of 1926. Hot and cold water in the toilets, electric light, a bell system controlled from the Headmaster’s Room. All these were sheer luxury compared with the outside yard toilets, paraffin lamps, a heating arrangement of open fires protected by fire-guards in Abermorddu. Most of the heat generated either went up the chimneys to warm the Abermorddu atmosphere or dissipated itself into the lofty ceilings.” The school did not actually have flush toilets until 1926 when they were fitted outside. They continued to present problems, especially in winter and it was not actually until 1965 that toilets were fitted indoors. It is clear from reading the centenary publication that the School Log Books are a rich source of information and future articles may explore these more fully. Some of the great events of the Victorian times and the first half of the twentieth century impacted upon the life of the school. The Relief of Ladysmith during the Second Boer War (1899) was a public holiday; there is reference to the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, the start of the Great War and also the arrival of evacuees from Merseyside during the Second World War. As was often the case in rural communities, attendance at school fluctuated with the harvests and weather, although epidemics also had an impact. As the population grew, with further industrialisation, accommodation became a problem. There is reference to one class being taught in a local chapel. This may have been the ‘Tin Tot Chapel’, which formerly stood by Coronation Terrace and was also used for Sunday School. Little has been recorded about the history of Abermorddu although there are local people who can still remember where some of the shops were along Hawarden Road and other features of note. I welcome any local reminiscences for future articles which might help to preserve this part of our heritage. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523.  At first sight a meeting of Flintshire County Council’s Cabinet may not appear to be the obvious topic for an article on Our Heritage. The particular meeting in question was on 23rd October with Cabinet members facing a lengthy agenda of 626 pages. Somewhere, buried in the pages of the agenda, was an issue of great importance to the local heritage. Business was, and usually is, brisk with significant decisions being made on recommendations of key importance to residents. It took a mere two and a quarter hours to reach Agenda Item 15 on page 585. There were less than a handful of observers, but they were waiting with baited breath: Our Heritage and our future were both at issue. The Agenda item was entitled ‘Centenary Fields’ and it carried a clear officer recommendation that Cabinet agree to four sites in Flintshire being submitted to Fields in Trust as Centenary Fields. The sites in question were:

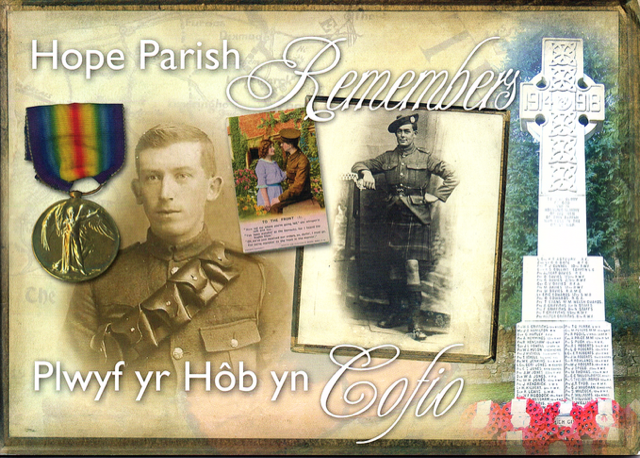

Further recommendations were that Cabinet authorise the Deed of Dedication with Fields in Trust to be signed on behalf of the Council, if the application is successful, and also that Cabinet agrees to a series of events being held to mark the occasion of the sites being designated as Centenary Fields. The Centenary Fields programme, launched as Fields in Trust, is an initiative to honour the memory of those who lost their lives during World War One by safeguarding valued, open spaces in perpetuity for future generations. The programme aims to have at least one green space in each local authority area. In order to meet the criteria for acceptance the site must have a connection with World War One and must also be accessible to members of the local community. It is to the credit of members of Hope Community Council that they nominated the Willows as such a site to be considered. Following consultations with Flintshire’s Legal, Estates, Streetscene and Planning Services a final list of sites to be nominated as Centenary Fields was agreed and the Willows was on the list for Cabinet consideration. It has to be said that the community should also be grateful to the local team of members of www.flintshirewarmemorials.com and also to those who worked on the 2014 HLF-funded project which commemorated the local servicemen who fell in World War One. A copy of the local booklet ‘Hope Parish Remembers’ had been made available to officers to support the case. Project group member Andrew Moss produced a map which shows that the Willows playing Field was at the centre of a community which suffered to loss of sixty local servicemen. That map can be viewed here. The officers now entrusted with the task of submitting the application to Fields in Trust also wanted to know about current uses of the Willows Playing Field and members of the local community who responded to the appeal, made on social media sites, by submitting photographs have also helped. The Willows Playing Field is an important part of our heritage which deserves to be preserved for future generations. It is an area which has been subjected to various planning applications which have raised questions about its future. It was extremely heartening to see that the Flintshire Cabinet gave unanimous agreement to the recommendation for The Willows to be submitted to Fields in Trust as a Centenary Field. Members spoke about the need for this to be taken off the list of Flintshire’s assets which are available for sale and for any uncertainty about the site, in its entirety, to be ended. If the application is successful the existing arrangements for managing and maintaining the site will remain the same. Once the Deed of Dedication has been signed the resulting restriction will be required to be registered with the Land Registry. The decision will be legally binding, protecting the site from being considered as a disposable asset. Consent would be required from Fields in Trust for any future change of use outside the terms of the agreed Deed. There is a target date for all Deeds of Dedication to be completed by May 2019. If successful the Willows will receive a commemorative plaque to be displayed at the field.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523

A cry of agony with a message of Hope: First World War Fallen Servicemen Remembered in Hope Cemetery. The Old Cemetery of Hope is a testament to the cry of agony which the community gave out because of the tremendous loss due to World War I. It bears not only the bodies of five servicemen who lost their lives but also of the heartfelt loss of those whose bodies lie elsewhere. Family graves remember the Fallen of their family. The inscriptions represent a snapshot of a global conflict. What follows is a 25-question quiz based on the graves, several of which are now difficult to locate and are also becoming increasingly difficult to decipher. First we have the actual graves of those who lost their lives:

Pte Andrew Malcolm Martin was a railway platelayer before the War and was a member of the Royal Defence Corps which provided troops for security, guard duty and POW camps in the UK. Records show that he served 3 years and 161 days. He died of vascular disease of the heart and TB of Sternum in 1921, aged 49, and was added to Caergwrle Memorial. Although there is no evidence that he served overseas there was local recognition that the War contributed to his death. The grave shows that his family had suffered the loss of a son in 1918. How old was the son when he died? (1 mark) Pte Ralph Henshaw worked at Pentre Farm. He was injured, probably by machine gun fire, at Battle of Ancre (Somme) and was rescued from No Man’s Land. At the time it was believed that he could be saved so he was sent to Bethnal Green Hospital. However, he died on 18th Nov 1916, aged 20. In disbelief family members asked for the coffin to be opened. They were shocked to see that he had missing limbs. It is likely that septicaemia had set in and amputation did not save him. Such was the fate of many before the development of penicillin. Examine the family graves. How old was Ralph when he lost his mother and his father? (2 marks) Pte Thomas Griffiths was a coal miner before the War. He served and survived conflict in Gallipoli and Egypt. Thomas returned home but died on 23rd July 1919 of Malaria and Pneumonia, aged 41. What is the service number on his military grave? (1 mark) Pte Albert Roberts had also been a coal miner and hewer before the War. He was wounded in France and was entitled to wear the Silver War Badge to show that he was a wounded soldier. Those who were not serving abroad were subjected to accusations of cowardice and given white feathers by local girls. He died of his wounds on 10th January 1920 aged 30 and was given military funeral. Both he and Pte Thomas Griffiths belonged to a long-established regiment which had an archaic spelling. What was that regiment? (1 mark) Pte John Kendrick was yet another coal miner before War. He suffered chest problems which were aggravated by military service. There is no evidence that he was well enough to serve broad. He died 2nd November 1918 of chronic fibrosis of the lung and influenza, aged 27, four days before the birth of daughter, Elizabeth. To which army corps did he belong? (1 mark) Fallen Soldiers Remembered by Inscriptions: Pte Alfred Hemmings was a tailor before War. He joined 5th Bn RWF and was killed on 26th March 1917 in First Battle of Gaza. Twenty-two other Flintshire servicemen lost their lives in this battle. There was criticism of the commanding officer’s decision to withdraw when they could have won: ‘we grasped defeat from the jaws of victory.’ He is remembered on a marble family gravestone which is difficult to read. Who was his sister? (1 mark) Walter Jenkins is remembered on the grave of Llewelyn Jenkins. He died on 3rd July 1916, aged 37. He was born in Wrexham and spent his childhood in Hawarden and Hope. He was married and lived in Derby Road, Caergwrle for a while before moving to Rotherham. His parents and siblings lived in Caergwrle and he joined up in Wrexham. Where, according to the memorial, was he killed? (1 mark) Gunner George Vincent Davies was a member of large local family with several current-day relatives. He worked for HM Factory before War and then joined the Royal Field Artillery. He was killed on 11th September 1917 at Ypres as a result of a gas shell explosion in door of dug-out where he and others were sheltering from attack. Give the names of his mother and father. (2 marks) Pte William Jones Roberts worked at Rhanberfedd Farm. He joined 10th Bn RWF (possibly with Ralph Henshaw) and was a member of Presbyterian Sunday School. He was killed in France 18th June 1917, aged 24. In which local building did his family live? What is the building used for today? (2 marks) Pte Sidney Pugh had been a carpenter before War, his family being associated with Pugh’s Yard. He joined 5th Bn RWF and was posted to Gallipoli. They landed at Suvla Bay on 9th August 1915. The battalion crossed the extensive mud of the dry Salt Lake on 10th and headed towards Scimitar Hill. There were many causalities on 10th including local man John Douglas Jones-Davies. Sidney was hit by a shell whilst bearing a stretcher on 11th, aged 23. It was the second day of his involvement in the War. He died knowing that his wife, Myfanwy, had already died. How old was she when she died? (1 mark) Lance Corporal Harry Asbury is remembered on an edging stone on the Bevan family grave. He was in the building trade before the War and was actually at home on leave in May 1918. However he was sent, as part of secret Syren Forces, to Murmansk, Russia. Initially troops were sent to stop Germans using Russian ports but they became secretly involved in the Russian Civil War as opponents of Bolshevism, a conflict that continued after the end of the First World War. He died, in an accidental barracks fire on 1st February 1919, aged 36. What was the name of his wife? (1 mark) Sapper Albert Davies was a railway worker before War and became part of 279th company of the Royal Engineers. Records show that he was at part of the battle front where manual workers fought the Germans ‘with picks and shovels’. This is likely to have been the German Spring Offensive ‘Operation Michael’, which followed the withdrawal of Russia from the War. The failure of Operation Michael is considered to have been the beginning of the end of the War. Albert survived the offensive but he fell victim of the global influenza pandemic and died of pneumonia in France. Where, according to the grave, did his family live? (1 mark) Pte Thomas Evans MM was the son of a local timber merchant. He was one of four men awarded the Military Medal following action at Langemark in Ypres Salient. Welsh Guards were subject to a counter attack and severe shelling. The line was held by men squatting, soaked to the skin in mud-filled shell holes. Four men were noted as having remained on duty throughout the action though wounded. He died the next day on 5th September 1919. The family grave gives the names of two children who died in infancy. Who were they? (2 marks) Cpl. William Frederick Maddock worked as a brewery clerk before the War and his family were associated with Red Lion in Hope. He served in 17th Bn of RWF at Somme and was killed in action on 9th July 1916. He was part of 38th Welsh Division and died at the Battle of Mametz Wood. What is the epitaph that follows the inscription of his name of the grave stone? (1 mark) Second Lieutenant Harry Kilvert was the son of a farmer and was born in Shropshire. He married Mary Woolfall whose family lived in Hope. He died on 1st August 1917, aged 33, and is buried at Bailleul Cemetery, France. He served in France and died of wounds received at Battle of Messines. Who is the first member of the Woolfall family to be named on the grave? (1 mark) Pte John William Roberts was the son of Joseph and Martha Roberts of Laburnum Cottage, Penymynydd. He saw action at Salonika and then joined those fighting in Palestine. He died 10th March 1918 in Palestine, aged 34. What is the epitaph that follows his name on the grave of Martha Roberts? (1 mark) Capt. Charles Cadwalladr Trevor-Roper and Pte Geoffrey Trevor-Roper were members of the family associated with Plas Teg who are also remembered on a plaque in Hope Parish Church. Regardless of social standing the War took its toll. Both died at Ypres within weeks of each other. The gravestone takes the form of a Crucifix atop a triple plinth – the symbol of Calvary. The inscriptions are becoming faded. When did each of them die? (2 marks) Driver William Alfred Jones was the son of Alfred and Elizabeth Jones of Hope. His father ran a grocery shop next to Red Lion and William was employed as a carter in the family business in 1911. He was killed in France on 26th September 1918, aged 29. His name is to be found on a family grave beneath a yew tree. The epitaph is a paraphrased passage from St Paul’s letter to the Philippians. What is it? (1 mark) The family of Sgt. Percy Bellis lived in Penyffordd but Percy moved to Shotton where he became a sheet steel worker before War. Reports state that he showed bravery whilst killed in action at the Battle of Loos 25th September 1915; the battle noted for men playing football as they ran towards the Germans. He is remembered on the Hawarden Memorial. The gravestone is next to a yew tree and the inscription is difficult to read and is worth preserving: Sleep on dear son in a foreign grave Your life for home and country you gave No mother stood near to say goodbye But safe in God’s keeping now you lie. The grave of Evan Hugh Jones is to the right of this grave. It serves to remind us of another tragedy that struck the locality. How did he die? (1 mark) Pte Arthur Griffiths died on 31st August 1918 having been killed in action at the Battle of the Somme, aged 35. He was the brother of T. G. Griffiths of Rose Cottage, Penyffordd. He died on 31st August 1916. The Griffiths family grave stone is in a poor condition. It has fallen down and the reference to Arthur is difficult to read. Where, according to the grave, did the family live? (1 mark) The Old Cemetery provides evidence of the tremendous cry that the community gave as a result of the catastrophic loss caused by the War but there is also an element of hope for the future. The snapshot represents one third of the Fallen on local memorials. The fact that we have to actively search for these graves means that the wound was eventually healed. No matter how great the loss communities have the capacity to show resilience and recover. The stories of the Fallen show that, at a time of great need, local people showed outstanding bravery and courage. Readers can learn more about our Fallen First World War servicemen from www.flintshirewarmemorials.com Although considerable attention is being given to servicemen of World War I it is important to recognise that he Old Cemetery of Hope also has the military graves of three Second World War servicemen. They are Corporal C Dixon on the Royal Engineers, Able Seaman Percy Norman Clark and Flight Sergeant Francis Richard Morris. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the policy of Flintshire County Council. Readers are welcome to contact the author with any news or views on the local heritage at [email protected] or by telephoning 01978 761 523. |

AuthorDave Healey Archives

December 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed